Excavations at Pine Ridge: Farmers and Hunters of the Ancient Great Plains

My first archaeological field experience was a field school through the University of Colorado at Boulder, studying pre-columbian archaeology on the northern great plains. The site we worked at sat a few miles from the White River, which bends south into Nebraska after running through the badlands of South Dakota.

My fellow students and I would hardly have been anyone's first picks for a month's hard labor in a field, and my professor must have expected as much. Our first night on the dig was spent in a local Pawnee earth lodge, sleeping around the pale moonlight of the smoke-hole at its' center. I remember waking up sometime in the early hours of the morning, seeing a centipede crawling passed my side-turned face, and drifting back off to sleep. In retrospect I think the earth lodge was meant to break us in, and it definitely accomplished the task. There's a level of cleanliness, a quickness to be disgusted that doesn't pair well with squatting in a ditch and sweating in the sun ten hours a day, or sleeping on a deerskin in an earth lodge.

The site in question had been nicknamed "The King Site," for the surname of the property owners. It was an early plains village site, which fell into an awkward carbon dating plateau period between A.D. 950-1050. This means that due to fluctuating ratios of C14 to C15 in the atmosphere, any readings between those two dates are difficult to distinguish. Now, in the archaeological chronology of the Great Plains, the year 950 roughly marks the end of the Plains Woodland Period and the beginning of the Plains Village Period. This transition was characterized by a shift to maize cultivation (from hunting and gathering) and the growth of semi-permanent villages. However, prior to this excavation there was no evidence that maize cultivation ever spread this far west onto the plains.

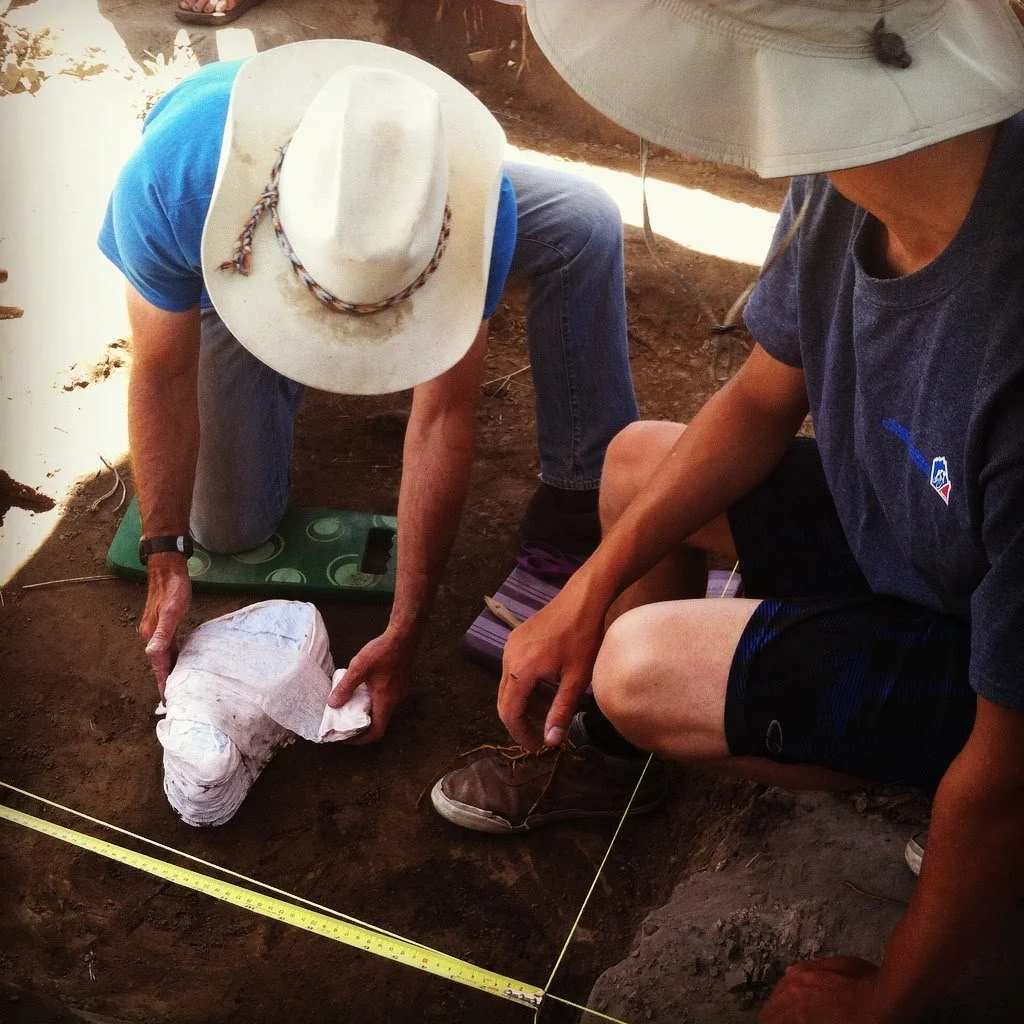

We excavated two features. One, a pottery kiln, was filled with animal bone, stone tools, charcoal, and other debris. It basically became a giant trash pit after the pot they had fired in it was finished. By the end of this dig, it also earned the honor of being the first fully excavated kiln on the plains. The other feature was a pit house. Pit houses are characteristic of the Plains Village Period, but not of the Plains Woodland period. This made it an important feature with which to date the site. The pit house was challenging to find, given that it had been built from impermanent materials. While pyramids and temples can be easily identified because their stones last for millenia, the only traces of the pit house we hoped to find were a slightly packed, discolored, round layer of earth (the living surface of the house) and a dark stain at the center where the hearth would have been. Of course, just because the kiln and the pit house were close to one another did not guarantee they were from the same occupation period. It was entirely possible that one came first, before people reused the same living site later on. Excitingly, we found burned maize in both features, which, while not conclusive evidence of farming (it could have been traded for) goes a long way towards proving that agriculture spread much further up the tributaries of the Missouri river than scholars believe. Combined with carbon dates from both features, we became fairly confident stating that both features came from the same occupation period.