Gandhi in the South African War

“We were marching towards Chievely Camp where Lieutenant Roberts, the son of Lord Roberts, had received a mortal wound. Our corps had the honor of carrying his body from the field. It was a sultry day,- the day of our march. Every one was thirsting for water. There was a tiny brook on the way were we could slake our thirst. But who was to drink first? We had proposed to come in after the tommies had finished. But they would not begin first, and urged us to do so, and for a while a pleasant competition went on for giving precedence to one another.” ~M.K Gandhi

I wrote a term paper recently discussing the role Gandhi played in the South African War, and I suspect the fictional readers of my blog may enjoy hearing this story.

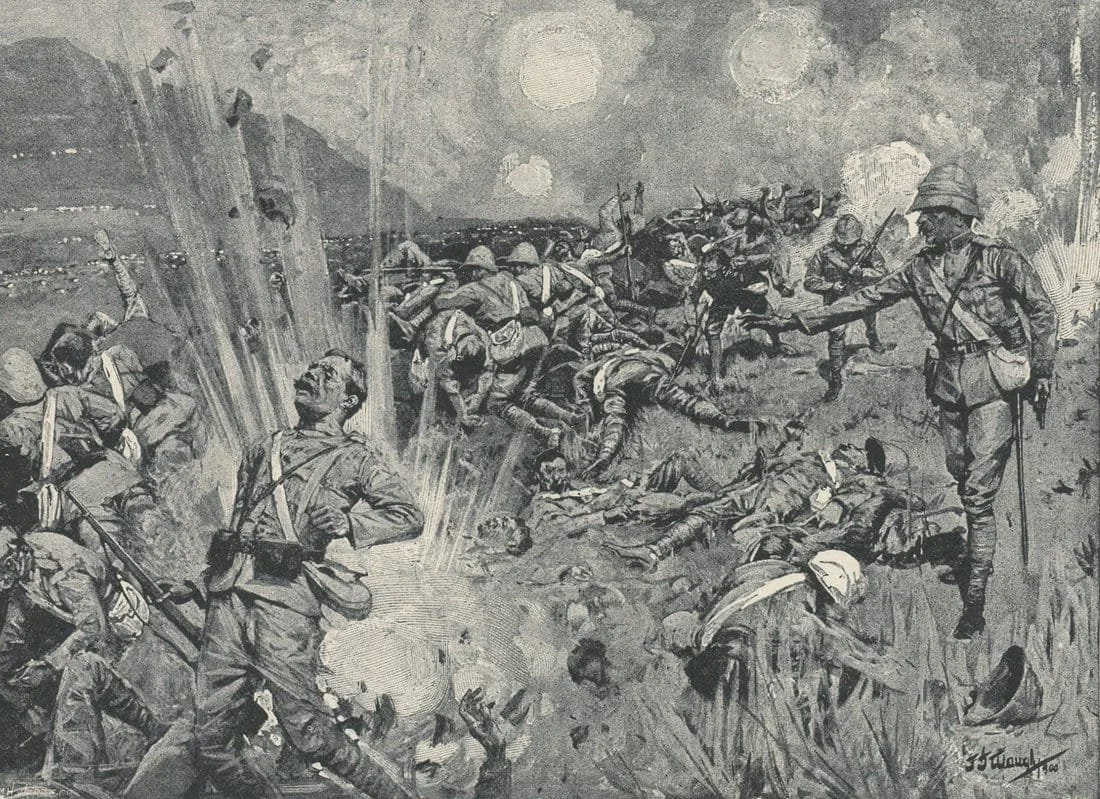

The South African War was fought from 1899-1902 between the British Empire on one side, and the Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic on the other side. Fought across the barren outback of western South Africa, the opening months of this conflict would serve as the backdrop against which Gandhi and other Indian leaders would debate what their own role in the conflict should be. The prediction I expect most readers to make at this point is that Gandhi would act as a political dissident, aiming to, in some small way, help the Boers (another people being oppressed by the British), or at least that he would remain neutral, opposing the war in some way.

Would it surprise you to learn, then, that Gandhi went on to be the driving force behind a thousand-man strong volunteer British ambulance corps composed entirely of Indian immigrants to British South Africa?

Gandhi justified this course of action with the following argument, quoted from his work Satyagraha in South Africa:

"Our existence in South Africa is only in our capacity as British subjects. In every memorial we have presented, we have asserted our rights as such..." "... It would be unbecoming our dignity as a nation to look on with folded hands at a time when ruin stared the British in the face, simply because they treat us ill here."

Characteristically, it seemed dishonest to Gandhi to think this without throwing his whole being into action, and he set to work gathering volunteers along with a few dozen other Indian community leaders. Initially they had no plan of action, and they sent a letter to the British government that included their signatures, certificates of medical training, and the simple assurance that they would do whatever work was asked of them. The British Empire's nose had been bloodied in the opening months of the war, and they were only too eager to accept the services of the Indian immigrants. Gandhi and his men were formed into the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps, and within a few months they had departed for the front line.

In Gandhi's account of the South African War he is shockingly positive, despite the brutality of the conflict and the danger that he and his men were under. He saw it as a unifying experience, one that brought together Indian Sihks, Muslims, Hindus, and their British comrades under the cause of service to the British Empire. As volunteer stretcher bearers, Gandhi and his men were not expected serve under fire. However, British officials would eventually recant on this promise and ask them to serve at the front line at the battle of Spion Kop.

Of this, Gandhi writes:

"We were only too willing to enter the danger zone and had never liked to remain outside of it."

The challenge of serving in this conflict cannot be overstated. Gandhi and his men were often required to carry wounded British soldiers as far as 25 kilometers in a day across dry, hilly terrain, under threat of attack from Boer guerillas.

I find this moment of Gandhi's life helps humanize him, and to triangulate one's understanding of his beliefs. His willingness to serve the British, his reasons for doing so, and the way he looked back on such a traumatic event with fondness are indicative of his singular nature. This story is a great example of how in many ways Gandhi was a supporter of aspects of British, and more broadly, European colonialism.