Napoleon’s Tomb Raiders

In may of 1798, a French armada set sail across the Mediterranean, heading for Alexandria. In command of the expedition was a 29 year old Napoleon Bonaparte- not yet emperor, but already a rising star in the French military. He had been given nearly 200 vessels and 13 ships of the line, alongside the newly formed Army of the Orient. This army was created to seize Egypt for France, from the clutches of the decrepit Ottoman Empire. (Fritze, 2015)

The Battle of the Pyramids, Louis-François, Baron Lejeune, 1808

More than 150 scholars also accompanied the expedition. These researchers, called the Scientific Commission, were to study every facet of Egypt, natural and human, modern, and ancient. Out of these men, though, only 3 were archaeologists. Archaeology was such a young discipline that it was largely still left to rich antiquarians to collect artifacts as curiosities, not as part of any scientific study

The Egyptian Expedition under the orders of Bonaparte, painting by Léon Cogniet, early 19th century

They came as conquerors, and from our perspective as looters, but they saw the remains of Ancient Egypt in a state that none of us will ever have a chance to experience. The sphinx was buried to its shoulders- many monuments still showed remains of their original paint- and two centuries of Egyptomania and looting had yet to strip the desert of its treasures. I want to share with you some amazing descriptions and illustrations, and ponder how much really separates me, a modern professional archaeologist, from those 19th century plunderers. I think the gap is narrower than you might think.

The Battle of Heliopolis by Léon Cogniet

While French soldiers, Ottoman Mamluke defenders, and local brigands fought in a chaotic and fast-moving campaign, the Scientific Commission scrambled to record everything they could. At the Battle of the pyramids, the French broke a Mameluke army under Murad Bey, who fled south to Upper Egypt. Napoleon sent General Louis Desaix chasing after him, with the scholar Dominique Vivante, Baron de Denon in tow. At Dendera, Denon saw the ruins of the Temple of Hathor, a sky goddess who was also associated with the worship of the dead.

The Temple of Hathor at Dendera by David Roberts

“I found, buried in a heap of ruins, a gate built of enormous masses covered with hieroglyphics. Through this gate I had a view of the Temple of Hathor. I wish I could here transfuse into the soul of my readers the sensation I experienced.” … “This monument seemed to me to have all the primitive character of a temple in the highest perfection.” ~Dominique Vivant, Baron de Denon (Russell, 2005)

Entering the temple, he was astonished by the carvings adorning the inside.

“On casting my eyes on the ceiling, I perceived zodiacs, planetary systems and celestial planispheres represented in a tasteful arrangement. I observed the walls to be covered with groups of pictures exhibiting the religious rites of the people, their labors in agriculture, the arts and their moral precepts.” ~Dominique Vivant, Baron de Denon (Russell, 2005)

Months later, when he had a chance to return, he knew he needed to study that beautiful ceiling again. Lying on his back in the darkened room, he sketched by candlelight.

“I began with what had been the principal object in my previous journey, namely, the celestial planisphere that occupies part of the ceiling of a little apartment built over the nave of the great temple. The floor being low and the room dark I was able to work for only a few hours of the day.” … ”The desire of bringing to the philosophers of my native country the copy of an Egyptian bas-relief of so much importance made me patiently endure the tormenting position required in its delineation.” ~Dominique Vivant, Baron de Denon (Russell, 2005)

Dendera’s zodiacal ceiling

This was the East Osiris Chapel, situated on the roof of the Temple of Hathor. The zodiacal ceiling he described is now housed in the Louvre in Paris, after having been looted by a French treasure hunter a couple decades later. This kind of two-faced behavior characterized the French adventure in Egypt. While figures like Denon made a serious effort at recording the ruins they encountered, just as many Frenchman dedicated themselves to private collecting and the bourgeoning antiquities trade.

"Denon's work aroused tremendous enthusiasm for archaeology, especially among the hydraulic engineers charged with improving Egyptian agriculture. The engineers were soon neglecting their own dull work and making a beeline for temples and tombs, recording architectural features, hieroglyphic inscriptions, and all the magnificent panoply of ancient Egypt. Pencils ran out, lead bullets were frantically melted down as substitutes, and a vast body of irreplaceable infromation was recorded for posterity. At the same time, they removed small antiquities by the hundreds from temple and tomb." (Fagan 1975: 53-54)

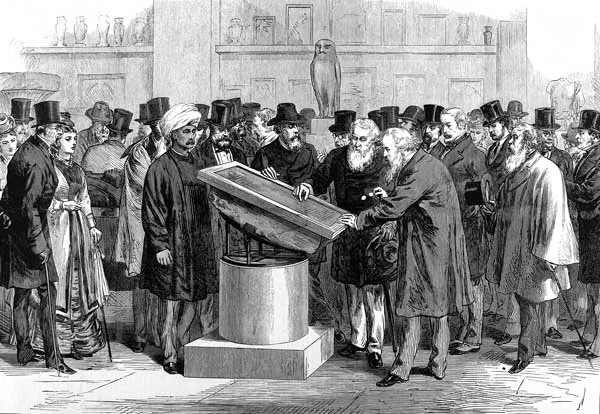

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the Second International Congress of Orientalists, held in London in 1874

The greatest discovery of the expedition was made by a soldier, not a scientist. While erecting coastal defenses in the Nile Delta, near the town of Rosetta, a soldier named D'Hautpoul stumbled across an inscribed granite stela beneath a pile of boulders (Fagan 1975: 50). On it were three versions of a decree- the first in Hieroglyphics, the second in demotic, the freehand version of the Egyptian script, and finally in ancient Greek. It was a miraculous find, because, it meant the Greek could be translated back into the Egyptian, and the mystery of hieroglyphics could finally be unlocked. So Napoleon's expedition culminated in the greatest single advancement ever made in Egyptology. But the Rosetta Stone was also fought over by Britain and France as a symbol of national pride, and has still not been returned to Egypt. For decades after his invasion, people like Bernardino Drovetti, the French consul to Egypt, and Henry Salt, Britain’s consul, continued the competition, and allowed widespread looting and collecting. "Their greed and rivalry became so intense that they reached an unspoken gentlemen’s agreement, if that is an appropriate description, to carve up the Nile Valley into 'spheres of influence.'" (Fagan 1975: 62)

One of the most talented treasure-hunters for the British side was the Great Belzoni, a former circus strong-man turned antiquities dealer. He uncovered Abu Simbel Temple from dozens of feet of sand, so the relief carvings inside could be recorded for the first time. He also sent a river of statues, mummies, and other treasures flowing to London. He even described crushing a mummy once when he sat on it. “I sought a resting place, found one, and contrived to sit; but when my weight bore on the body of an Egyptian, it crushed like a band-box.” (Fagan 1975: 98)

Portrait of Belzoni by Jan Adam Kruseman, 1824

At the same time, Champollion, the frenchman who deciphered the Rosetta Stone, was lobbying for better protection for these antiquities His pleas resulted in an Egyptian government ordinance published on August 15, 1835. On paper, it forbade all exportation of antiquities, and while unenforceable, it shows how this period led to the emerging concept of archaeological stewardship. (Fagan 1975: 170)

The funny thing is I’m only appalled at the way these people conducted archaeology because of the developments they contributed to. We are their intellectual descendants, and without those early archaeologists I would never have been taught modern methods of research. So in a sense, I’m standing on their shoulders, shouting down at them.

Modern archaeologists record what we dig up in excruciating detail. We deliver everything we find to museums, placing them in the public trust. But surely if we waited, future archaeologists could do the same digging, with better technology, gathering better data before destroying the site? After all, archaeological sites are destroyed when they’re excavated. The Society for American Archaeology’s first ethical principle is stewardship. “Stewards are both caretakers of and advocates for the archaeological record for the benefit of all people; as they investigate and interpret the record, they should use the specialized knowledge they gain to promote public understanding and support for its long-term preservation.”

But stewardship isn’t easy. It’s not as if putting an artifact in a museum is a perfect solution. Museums are stuffed to bursting in what is being called the curation crisis, and I’ve seen this firsthand. At the Smithsonian, they don’t even know everything they have- artifacts are often improperly stored, and many haven’t been looked at since they were first brought to the museum. There are endless rows of shelves of slowly decaying treasures, occasionally glimpsed by visiting researchers and collections interns. Is this what we mean by stewardship? It’s not like archaeologists don’t personally benefit from our control over antiquities, advancing our careers and reputations.

“If an artifact is to be dug out of the ground, I would want to see it in an archaeologist’s hands. What with their careful observation and skills of long term preservation, they are a far cry from pothunters. But since archaeologists hold themselves up as self-selected stewards, they invite close scrutiny.” ~Craig Childs

I doubt the ethics of archaeology will ever be clear. I think in terms of deep time, and I can’t imagine the knowledge we’ve gained lasting for too long, in the grand scheme of things. There are signs the rates of archaeological discovery are already in decline (Surovell et al., 2017). Imagine the empty hills and hollowed out ruins we leave to the archaeologists of future civilizations. The thing is, even after I think of that, I can’t help but feel excited about the next excavation. I don’t condone those early archaeologists. But I do understand them.

References:

Childs, C. (2013). Finders keepers: A tale of archaeological plunder and obsession. Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company.

Fagan, B. M. (1975). The rape of the Nile: Tomb robbers, tourists, and archaeologists in Egypt. Westview Press.

Fritze, R. H. (2015). Egyptomania: A history of fascination obsession & fantasy. Reaktion Books.

HOOCK, H. O. L. G. E. R. (2007). The British state and the Anglo-French Wars over antiquities, 1798–1858. The Historical Journal, 50(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0018246x06005917

Russell, T. M. (2005). The discovery of Egypt: Vivant Denon's travels with Napoleon's Army. Sutton.

Surovell, T. A., Toohey, J. L., Myers, A. D., LaBelle, J. M., Ahern, J. C., & Reisig, B. (2017). The End of Archaeological Discovery. American Antiquity, 82(2), 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2016.33