Why Hunt Ice Age Megafauna?

Among the most central topics of debate in Paleoindian archaeology is the role humans played in the extinction of dozens of species of Pleistocene animals, which disproportionally fall into the category of megafauna. In order to determine humanity’s role in these extinctions, the faunal record is pivotal in providing evidence for subsistence patterns, particularly with regard to large game animals. Beyond the debate of what Paleoindians were hunting, explaining why they chose to hunt certain animals may be necessary in order to illuminate their role in the end- Pleistocene extinctions of North America. To this end, it is useful to examine human big-game hunting in its ethnographic, ecological, and evolutionary contexts. Researchers in the field of Human Behavioral Ecology have identified two general perspectives to explain why foragers might hunt large game; on the one hand, it is possible big-game hunting is most often motivated by the need to provision one’s family, either by consuming and storing all of the meat acquired, or by sharing that meat with others in order to receive food in return at a later date. On the other hand, big-game hunting might be best explained as some form of costly signaling. Originally developed by Amotz Zahavi (1999), costly signaling supposes that behaviors which appear to reduce an organisms’ fitness may actually act to signal some otherwise cryptic quality of the organism to potential mates, ultimately improving their reproductive success.

North American Paleoindians have been imagined both as big-game specialists and as generalists consuming a wide variety of taxa both large and small. It is important to note that large game specialization does not imply that Paleoindians exclusively hunted large game. Specialization only implies that “smaller prey species are available but are relatively underutilized” (Surovell and Waguespack 2009: 84). Cannon and Meltzer (2004) argue that Paleoindians had a generalized diet which was highly site-dependent. Their study employs a faunal dataset including only those remains found in direct association with artifacts, found in archaeological features, or displaying evidence of burning or butchery. Surovell and Waguespack, alternatively, argue that Paleoindians were big-game specialists based on their own analysis of the Paleoindian faunal record (2009). Their approach employs a broader dataset, examining any faunal remains associated with Paleoindian site components, regardless of evidence of exploitation. This captures a wider range of body sizes, especially smaller taxa which were less likely to show direct evidence of exploitation. DeAngelis and Lyman find that Paleoindian hunting behavior cannot be easily characterized as specialized or generalized (2016), exhibiting great variety in different geographic contexts.

These different views are rooted in debates over the value of large game to hunter-gatherers more generally. For example, the interpretation of the Paleoindian faunal record hinges on applications of optimal foraging theory, ethnographic data, and evolutionary theory. Archaeologists who characterize Paleoindians as large game specialists treat large animals as high-ranked prey (Waguespack and Surovell 2003, Surovell and Waguespack 2009, Grimstead 2010). “Put simply, big animals are argued to be the preferred targets because they yield higher return rates than smaller ones” (Speth 2010: 150). Others have argued that while large game such as mammoth ought to be pursued when encountered, their relative rarity means that “foragers should have pursued a wide array of taxa including not only mammoth, but the full range of ungulates and some smaller game as well” (Byers and Ugan 2005: 1624). On the other hand, recently a number of researchers have made the case that large game may not be as high-ranked as has been supposed (Hawkes 1991, Bird et al. 2013, Lupo and Schmidt 2016). As we shall see, the value of large game, and the reasons hunter gatherers pursue large game are contested issues.

An ecological approach to understanding a foraging society’s diet must “initially assume that an activity’s value is related to its material consequences” (Kelly 2013: 73). Large game might be valued for the micro or macronutrients contained, or for the total caloric value. Protein intake over about 250g per day can lead to weight loss, nausea, and diarrhea, among other symptoms. Excessive protein consumption can cause serious health problems for pregnant women and their fetuses (Speth 2010, Kelly 2013). “Protein is also an inefficient way to provide energy to the body, whether for general metabolic needs or specifically for fueling the brain” (Speth 2010: 149). That being said, meat contains high-quality proteins, essential for healthy metabolic function. It is also quite nutrient-dense, containing minerals, vitamins, and glucose in a greater density than plant food. There are numerous ethnographic accounts attesting to the importance of meat, particularly fatty meat, and there is “a physiological reason for humans’ preference for fatty foods” (Kelly 2013: 74). While there are reasons for a forager to value meat, large game comes with some important complicating factors.

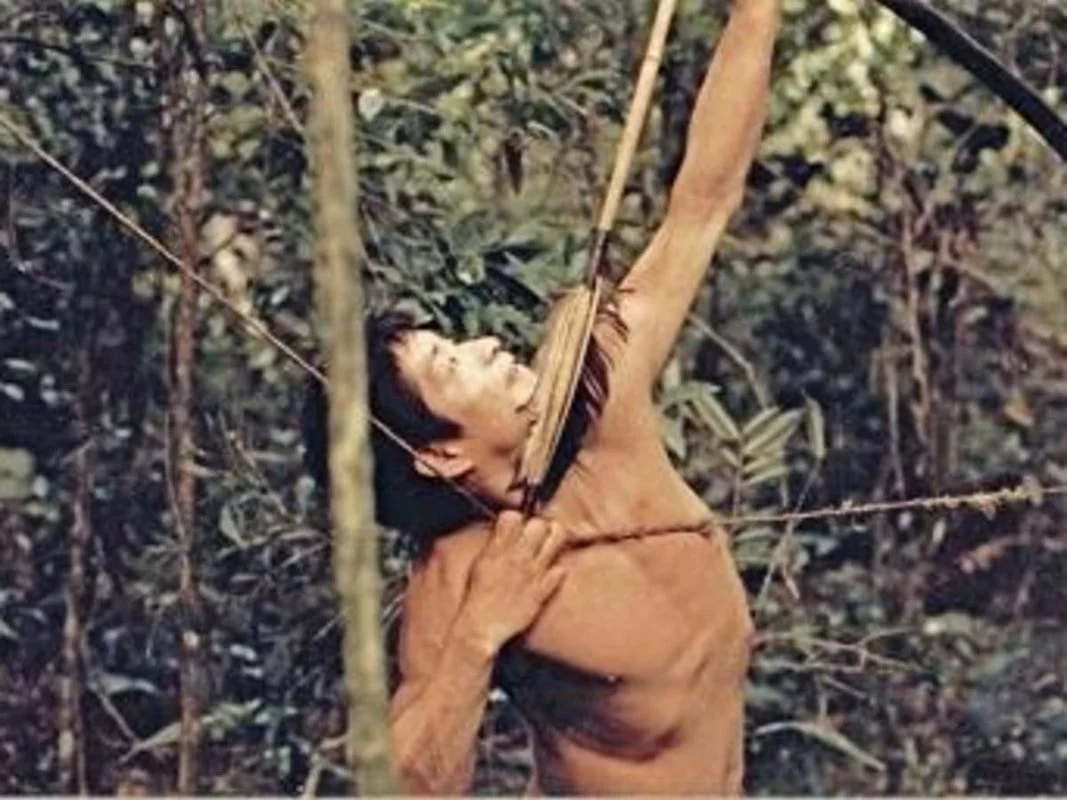

Among the most obvious complicating factors involved in big-game hunting is the risk associated with the activity. There are several different kinds of risk involved: Large game is risky to hunt in the sense that success rates tend to be lower than in the case of small game or plant foods. Additionally, large game is risky in the sense that large animals are often dangerous to hunt. Most importantly, large game hunting involves risk in that abundance can vary over time and space (Kelly 2013: 68). This element of risk imposes a gendered division of labor on hunting large game. Codding et al. (2011: 2502) argue that “when minimizing risk and maximizing energy trade-off with one another, we expect men’s foraging to focus on provisioning others through the unreliable acquisition of large harvests, while women focus on reliably acquiring smaller harvests to feed offspring.” Others have observed the same point. For instance, Kelly (2013: 222) points out that men’s foraging tends to target risky, high-return foods, while women tend to target predictable, low-return foods. “Large game hunting is a highly valued activity in foraging societies, even when it has appallingly low success rates. The reason is that meat from large game is always shared” (Kelly 2013: 221).

Large game animals are usually brought back into camp in large packages at a single moment, resulting in leftovers that the hunter and his family cannot immediately consume. “From the hunter’s perspective, the immediate value of the remaining meat is not worth fighting over but it is from the perspective of someone who is hungry” (Kelly 2013: 146). There are several explanations for how hunters might mitigate this problem. One possible explanation is reciprocal altruism, the idea that hunters provide meat to others when they experience a windfall with the expectation that the favor will be returned when they are the ones returning empty- handed (Gurven et al. 2000). Another explanation, tolerated scrounging, implies that hunters will tolerate theft in order to avoid conflict (Blurton Jones 1984). However, differential hunting abilities and the presence of free-loaders poses a collective action problem for good hunters. This point might predict frequent confrontations over kills, “but such events are virtually nonexistent” (Kelly 2013: 146). “Some men do contribute more to the soup pot than others without holding it against anyone” (Kelly 2013: 146). For some foragers, cultural norms help to preempt conflict over scrounging. Researchers have observed of the Hadza of Northern Tanzania that “hunters were not considered owners of the meat from the carcasses they acquired and did not control its distribution” (Hawkes et al. 2014: 607). These points have led some researchers to the conclusion that there must be other adaptive benefits to men who hunt large game. “Tolerated scrounging is common in the animal world, and its potential to cause harmful contests may be what, in the distant reaches of human evolution, motivated other forms of sharing that benefit the person who shares” (Kelly 2013: 147).

Kristen Hawkes has been a strong proponent (1990, 1991, 1993, Hawkes and Bird, 2002) of the idea that family provisioning and reciprocal redistribution cannot explain many male hunting decisions, particularly in the case of large game. Hawkes argues instead that large game hunting is motivated by other social benefits, and that “the occasional jackpots, much larger than a hunter and his family could consume, may confer greater reproductive benefit than a higher daily mean with no bonanzas” (Hawkes 1990: 146). This argument was initially based on observations of sharing behavior among the Aché, a foraging society in Eastern Paraguay. Aché men were often observed pursuing high-risk, high-reward large game that offered a lower caloric return rate than other options, such as foraging for palm fiber. As foragers returned to camp each day, food which came into camp in larger packages, “with greater daily acquisition variances across adults of the same sex” (Hawkes 1990: 147), was shared across the camp with no advantage to a forager’s nuclear family. This was particularly true for meat and honey. On the other hand, plant food and insects were observed to be preferentially shared among a foragers’ nuclear family. Hawkes et al. (2001, 2014) made similar claims about the Hadza of Northern Tanzania. For example, they observe that neither a Hadza man’s hunting success, nor the amount of time spent hunting can predict how much meat his family got from the kills of others. Hawkes proposed that men primarily hunt large game as a form of costly signaling, to “show off” to a wide range of companions in order to receive favorable treatment in return (Hawkes 1991, Hawkes and Bird 2002). Costly signaling theory predicts that a signal enhances an individual’s fitness when costs are linked to the qualities of the signaler, and the signal successfully advertises this fact to others (Bird et al. 2001). Among the Meriam, a Melanesian people of the Torres Strait, “successful turtle hunters signal strength, risk-taking, and (in the case of hunt leaders) a variety of cognitive and leadership abilities to potential allies, mates, and competitors” (Bird et al. 2001: 10).

Hunting turtles is extremely time consuming and difficult (Bird et al. 2001), and many recent studies have presented evidence that given the chance of a large animal evading a hunter, “the post encounter return rate from pursuit may be quite low, despite the potentially high yield” (Bird et al. 2013: 156). Many large terrestrial animals such as African elephants (Loxodonta africana) are extremely dangerous to hunt, and “are lower ranked and less efficient to acquire than many smaller-sized animals irrespective of their encounter rates” (Lupo and Schmidt 2016: 185). This point raises doubts that prey size can be used to estimate profitability and prey rank in zooarchaeological analyses. Where provisioning fails to provide sufficient incentive to pursue large game, “sociopolitical currencies can provide incentives” (Lupo and Schmidt 2016: 186). Jones et al. (2013) demonstrate that Martu hunters in Western Australia pursue Hill Kangaroo despite the species possessing a lower expected utility than other, smaller species. Good Martu hunters provide meat to their companions in order to acquire authority and religious knowledge (Kelly 2013: 244). On the other hand, Martu hunters frequently encounter camels but rarely pursue them, despite camels being a high-ranked prey animal posing little physical danger to the hunters. In this case Bird et al. (2013: 162) suggest that the highly formalized ways in which the Martu share food make camel difficult to distribute.

In Western North American prehistory, Hildebrandt and McGuire (2002, 2005) have been pivotal to the introduction of costly signaling theory. They observe that during the middle and late Holocene in California, there was an expansion in large game hunting even as population densities increased. “Under such circumstances, optimal-foraging theory would predict a decline in foraging efficiency, resulting in a greater reliance on the hunting of smaller prey” (Hildebrandt and McGuire 2002: 231). The authors then suggest that other fitness benefits available to males could have motivated hunting large game at the expense of family provisioning. They state that while zooarchaeological research in isolation cannot differentiate between “foraging constructs such as the Central Place Foraging Patch Choice Model from those derived from the social context of large-game hunting”, a more thorough contextual analysis of multiple lines of evidence can help make such a differentiation (Hildebrandt and McGuire 2002: 250). Hildebrandt and McGuire observe that in the case of the Meriam turtle hunters of the Torres Strait, there is “a “high correlation between periods of peak turtle hunting and large ceremonial gatherings” (2005: 699). As costly signaling requires some audience beyond a small family band, there ought to be a threshold of group size and settlement aggregation which must be exceeded for signaling to emerge.

Costly signaling has faced criticism for a number of reasons, from debates over proponents’ ethnographic understanding of foraging societies to root theoretical critiques. Costly signaling implies that some underlying characteristics are being displayed by big-game hunting. Proponents of costly signaling have proffered a wide range of possibilities, many of them vague and poorly defined. Bird and Smith (2005) suggest that these characteristics might include intelligence, skill, and physical fitness. In the case of a characteristic like physical fitness, it may be easy enough to assess visually that there is no need for a more subtle signaling mechanism. “If hunting is indeed an honest signal, more work must be done to show it is correlated with an otherwise cryptic but adaptively relevant quality” (Stibbard-Hawkes 2018: 181). Costly signaling theory also requires good evidence that big-game hunting is costly, and that it is a less efficient form of provisioning than small-game hunting or gathering.

Hawkes (1991) argued that Aché men could gain energy more easily by foraging for palm starch as opposed to hunting. However, more recent evidence shows that “only one in 35 encountered palms has exploitable starch” (Gurven and Hill 2009: 52), and it is unlikely a purely plant-based diet would provide higher returns than one incorporating hunting. Wood and Marlowe (2014) have argued that Hawkes and others have described their ethnographic data on the Hadza incorrectly. For example, they point out that a major false premise behind a 2014 article by Hawkes et al. is that Hadza men “were large game specialists, spending 100% of their time out of camp solely hunting large game” (Wood and Marlowe 2014: 627). In fact, they point out that “95% of the food items that men brought to camp were foods other than large game” (Wood and Marlowe 2014: 627). They argue that Hadza men seeking to maximally provision their families are right to pursue large game alongside other resources, given that the “pre-sharing profitability of large game hunting is more than 15 times higher than the rate Hawkes et al. compute” (Wood and Marlowe 2014: 627)). Skilled Hadza hunters were observed to provide more food to their immediate family than poor hunters, and the authors’ results support big-game hunting as a form of family provisioning. Additionally, given that Hadza campsites ordinarily contain extended family of the hunter, there is an element of inclusive fitness to meat redistribution.

Ugan and Simms have taken issue with work by Bird et al. (2009) among the Martu of Western Australia. They point out that the relationship between body size and post-encounter returns among Martu prey is largely dependent on whether tracking is included as handling time when calculating return rates. Bird et al. count tracking as part of pursuit costs, with the assumption that tracking requires one to follow an animal’s tracks to the exclusion of all else. Ugan and Simms point out that “we are not told if hunters actually encounter and pass by game while tracking” (Ugan and Simms 2012: 180). This is important because “if hunters do not encounter any alternate prey to pursue, then exclusivity is merely epiphenomenal” (Ugan and Simms 2012: 180). If hunters do not follow large game to the exclusion of all other options, the cost of pursuit would be dramatically lower. Additionally, they point out that Bird et al. (2009) do not make their treatment of failed tracking attempts explicit. If handling time begins from the moment a hunter starts tracking his prey, failure to locate an animal may have been listed as a failed pursuit, and counted against post-encounter return rates (Ugan and Simms 2012: 180). Given that “nothing in the Martu analysis suggests that the body size-return rate relationship observed there is part of a more general pattern” (Ugan and Simms 2012: 181), the authors argue that body size is still a good measure of prey rank.

Others have taken issue with applications of costly signaling theory in archaeology. Codding and Jones have responded to McGuire and Hildebrandt’s work studying Western North American prehistory. They argue that McGuire and Hildebrandt make a number of unsupported generalizations on the nature of the ethnographic record. These generalizations include the idea that big-game hunting is primarily undertaken for prestige purposes, as well as an assumption that prestige hunting can have a substantial impact on the faunal residues in the archaeological record. They assert that in any given society, only a small percent of individuals tend to be actively involved in costly signaling behavior. This makes it unlikely that costly signaling could have acted “as the driving force underlying dramatic cultural changes including the rapid cultural transformations in the Great Basin at the end of the Middle Archaic discussed by McGuire and Hildebrandt” (Codding and Jones 2007: 350). Deanna Grimstead has applied the central place foraging model to prehistoric archaeological contexts. Paired with a “caloric expenditure formulae, derived from human energetics and locomotion research” (Grimstead 2010: 61), Grimstead argues that large game animals provide very high return rates in comparison to small game when procurement distances are high. This is primarily due to humans’ well-adapted physiology for carrying heavy burdens over long distances. In order to demonstrate that Paleoindian big-game hunting can be best explained by costly signaling theory, researchers must first demonstrate conclusively that ethnographic data shows big-game hunting to be relatively costly, and this matter is not settled (Grimsted 2010: 61). They must also demonstrate the presence of dietary alternatives that provide better provisioning opportunities, along with evidence that those alternatives were passed up in favor of large game (Codding and Jones 2007: 351). This problem, at least, may be resolved through further study of the faunal record, particularly at campsites in which a more complete picture of Paleoindian diet might be preserved.

It is quite possible that both provisioning and costly signaling factor into the decision to hunt big-game, depending upon the context. For example among the Hadza, “men’s hunting and sharing behavior might best be explained as a provisioning strategy when they are feeding their own children, but something more akin to costly signaling when they have stepchildren” (Speth 2010: 161). Along a similar line, Wood (2006) has suggested that unmarried Hadza men may be more likely to engage in risky signaling behavior, while those with children may be more likely to focus on provisioning. Among the Ju/‘hoansi of Namibia, hunting serves different purposes at different life stages, with young men motivated by the need to signal positive attributes, while older men often cite provisioning as their primary motivation for hunting large game (Weissner 2002: 418). Gurven and Hill argue that a large portion of hunting is motivated by provisioning, with additional motivations including “contingent reciprocity, social insurance, ‘cooperative breeding,’ and costly display” (Gurven and Hill 2009: 62).

Arriving at a consensus explanation for hunter-gatherer big-game hunting has been hard enough when examining ethnographic accounts, but when considering Paleoindian subsistence, the waters are muddied by our imperfect understanding of the Pleistocene environment. Kelly and Todd (1988) point out that hunting could have been a valuable adaptation to conditions characterized by a dearth of neighboring groups with knowledge of local resource geography, and “high residential, logistical, and range (territorial) mobility” (Kelly and Todd 1988: 231). Conditions could very well have produced a suite of behaviors “unlike that of any modern hunter-gatherers” (Kelly and Todd 1988: 231). Surovell and Waguespack (2009: 84) remark that “subsistence hunters documented in the modern era occupy ecosystems that have been inhabited by humans for thousands of years, and human populations likely exist at relatively high density levels.” While few recent ethnographic accounts in “marginal” environments document large game specialization, Pleistocene environmental conditions may have facilitated such specialization. “According to the diet-breadth model, specialized subsistence strategies should be present in environments where return rates for highly ranked prey species far exceed those of low-ranked items, and high-ranked taxa are encountered frequently” (Waguespack and Surovell 2003: 337). On the other hand, “a generalized strategy would be expected in environments where high-ranked taxa are infrequently encountered, where high-ranked taxa are rarely successfully captured, or where little variability exists in return rates among prey items” (Waguespack and Surovell 2003: 337). Speth et al. (2013: 114) note that “Paleoindian hunters did kill big animals, including megafauna, and sometimes in large numbers. But we don’t yet know how often they did it over the course of the year, and we know even less about the recurrence of successful kills from year to year.” Surovell and Waguespack (2009: 85) lament of the current archaeological record that “it is not large, it is likely biased, and it is not well-studied.” Expansion of this record, then, is of paramount importance.

While there is good ethnographic evidence that men do not hunt large game solely for provisioning, it does seem that large game can still be characterized as a high-ranked resource. The collective action problem posed by large game is not an intractable one, and “it now seems clear that the family of a good hunter receives more meat from the husband’s efforts than do other families” (Kelly 2013: 222). Costly signaling is also well documented ethnographically, and best explains hunting decisions among young and unmarried men, but does not seem to explain the majority of ethnographic big-game hunting behavior. For this reason it seems that costly signaling would remain a secondary explanation for a faunal record that displayed evidence of large game specialization.

Bird, Douglas W., Brian F. Codding, Rebecca Bliege Bird, David W. Zeanah, and Curtis J. Taylor. “Megafauna in a Continent of Small Game: Archaeological Implications of Martu Camel Hunting in Australia's Western Desert.” Quaternary International 297 (2013): 155–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.01.011.

Bird, Douglas W., Rebecca Bliege Bird, and Brian F. Codding. “In Pursuit of Mobile Prey: Martu Hunting Strategies and Archaeofaunal Interpretation.” American Antiquity 74, no. 1 (2009): 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/s000273160004748x.

Bird, Rebecca, Eric Smith, and Douglas Bird. “The Hunting Handicap: Costly Signaling in Human Foraging Strategies.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 50, no. 1 (2001): 96– 96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002650100375.

Bird, Rebecca Bleige, and Eric Alden Smith. “Signaling Theory, Strategic Interaction, and Symbolic Capital.” Current Anthropology 46, no. 2 (2005): 221–48. https://doi.org/ https://doi-org.libproxy.uwyo.edu/10.1086/427115.

Blurton Jones, Nicholas G. “A Selfish Origin for Human Food Sharing: Tolerated Theft.” Ethology and Sociobiology 5, no. 1 (1984): 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0162-3095(84)90030-X.

Byers, David A., and Andrew Ugan. “Should We Expect Large Game Specialization in the Late Pleistocene? An Optimal Foraging Perspective on Early Paleoindian Prey Choice.” Journal of Archaeological Science 32, no. 11 (2005): 1624–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jas.2005.05.003.

Cannon, Michael D., and David J. Meltzer. “Early Paleoindian Foraging: Examining the Faunal Evidence for Large Mammal Specialization and Regional Variability in Prey Choice.” Quaternary Science Reviews 23, no. 18-19 (2004): 1955–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.quascirev.2004.03.011.

Codding, Brian F., and Terry L. Jones. “Man the Showoff? Or the Ascendance of a Just-so-Story: A Comment on Recent Applications of Costly Signaling Theory in American Archaeology.” American Antiquity 72, no. 2 (2007): 349–57. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/40035818.

Codding, Brian F., Rebecca Bliege Bird, and Douglas W. Bird. “Provisioning Offspring and Others: Risk–Energy Trade-Offs and Gender Differences in Hunter–Gatherer Foraging Strategies.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278, no. 1717 (2011): 2502–9. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.2403.

Deangelis, Joseph A., and R. Lee Lyman. “Evaluation of the Early Paleo-Indian Zooarchaeological Record as Evidence of Diet Breadth.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 10, no. 3 (2016): 555–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12520-016-0377-1.

Grimstead, Deanna N. “Ethnographic and Modeled Costs of Long-Distance, Big-Game Hunting.” American Antiquity 75, no. 1 (2010): 61–80. https://doi.org/ 10.7183/0002-7316.75.1.61.

Gurven, Michael, Wesley Allan-Arave, Kim Hill, and Magdalena Hurtado. “‘It's a Wonderful Life’: Signaling Generosity among the Ache of Paraguay.” Evolution and Human Behavior 21, no. 4 (2000): 263–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/ S1090-5138(00)00032-5.

Gurven, Michael, and Kim Hill. “Why Do Men Hunt?” Current Anthropology 50, no. 1 (2009): 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/595620.

Hawkes, Kristen. “Why Do Men Hunt? Benefits for Risky Choices.” Essay. In Risk and Uncertainty in Tribal and Peasant Economies, edited by Elizabeth Cashdan. Boulder: Westview Press, 1990.

Hawkes, Kristen. “Showing off: Tests of an Hypothesis about Men's Foraging Goals.” Ethology and Sociobiology 12, no. 1 (1991): 29–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0162-3095(91)90011-E.

Hawkes, Kristen, James F O'Connell, and Nicholas G Blurton Jones. “Hunting and Nuclear Families: Some Lessons from the Hadza about Mens Work.” Current Anthropology 42, no. 5 (2001): 681–709. https://doi.org/https://doi-org.libproxy.uwyo.edu/10.1086/322559.

Hawkes, Kristen, and Rebecca Bleige Bird. “Showing off, Handicap Signaling, and the Evolution of Men's Work.” Evolutionary Anthropology 11, no. 2 (2002): 58–67. https:// doi.org/ https://doi-org.libproxy.uwyo.edu/10.1002/evan.20005.

Hawkes, Kristen, James F. O’Connell, and Nicholas G. Blurton Jones. “More Lessons from the Hadza about Men’s Work.” Human Nature 25, no. 4 (2014): 596–619. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12110-014-9212-5.

Hildebrandt, William R., and Kelly R. McGuire. “The Ascendance of Hunting During the California Middle Archaic: An Evolutionary Perspective.” American Antiquity 67, no. 2 (2002): 231–56.

Hill, Kim, Hillard Kaplan, and Kristen Hawkes. “On Why Male Foragers Hunt and Share Food.” Current Anthropology 34, no. 5 (1993): 701–10. https://doi.org/10.1086/204213.

Jones, James Holland, Rebecca Bliege Bird, and Douglas W. Bird. “To Kill a Kangaroo: Understanding the Decision to Pursue High-Risk/High-Gain Resources.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280, no. 1767 (2013): 20131210. https://doi.org/ 10.1098/rspb.2013.1210.

Kelly, Robert L., and Lawrence C. Todd. “Coming into the Country: Early Paleoindian Hunting and Mobility.” American Antiquity 53, no. 2 (1988): 231–44. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/281017.

Kelly, Robert L. The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers: The Foraging Spectrum. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Lupo, Karen D., and Dave N. Schmitt. “When Bigger Is Not Better: The Economics of Hunting Megafauna and Its Implications for Plio-Pleistocene Hunter-Gatherers.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 44 (2016): 185–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jaa.2016.07.012.

Mcguire, Kelly R., and William R. Hildebrandt. “Re-Thinking Great Basin Foragers: Prestige Hunting and Costly Signaling during the Middle Archaic Period.” American Antiquity 70, no. 4 (2005): 695–712. https://doi.org/10.2307/40035870.

Speth, John D. The Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting Protein, Fat, or Politics? New York, NY: Springer New York, 2010.

Speth, John D., Khori Newlander, Andrew A. White, Ashley K. Lemke, and Lars E. Anderson. “Early Paleoindian Big-Game Hunting in North America: Provisioning or Politics?” Quaternary International 285 (2013): 111–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.quaint.2010.10.027.

Stibbard-Hawkes, Duncan N. E. “Costly Signaling and the Handicap Principle in Hunter- Gatherer Research: A Critical Review.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 28, no. 3 (2019): 144–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21767.

Surovell, Todd A, and Nicole M. Waguespack. “Human Prey Choice in the Late Pleistocene and Its Relation to Megafaunal Extinctions.” Essay. In American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene, edited by Gary Haynes, 77–104. Springer, 2009.

Ugan, Andrew, and Steven Simms. “On Prey Mobility, Prey Rank, and Foraging Goals.” American Antiquity 77, no. 1 (2012): 179–85. https://doi.org/ 10.7183/0002-7316.77.1.179.

Ugan, Andrew. “Does Size Matter? Body Size, Mass Collecting, and Their Implications for Understanding Prehistoric Foraging Behavior.” American Antiquity 70, no. 1 (2005): 75– 89. https://doi.org/10.2307/40035269.

Waguespack, Nicole M., and Todd A. Surovell. “Clovis Hunting Strategies, or How to Make out on Plentiful Resources.” American Antiquity 68, no. 2 (2003): 333–52. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/3557083.

Wiessner, Polly. “Hunting, Healing, and Hxaro Exchange: a Long-Term Perspective on !Kung ('Ju/'Hoansi) Large-Game Hunting.” Evolution and Human Behavior 23, no. 6 (2002): 407–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(02)00096-x.

Wood, Brian M. “Prestige or Provisioning? A Test of Foraging Goals among the Hadza.” Current Anthropology 47, no. 2 (2006): 383–87. https://doi.org/https://doi-org.libproxy.uwyo.edu/ 10.1086/503068.

Wood, Brian M., and Frank W. Marlowe. “Toward a Reality-Based Understanding of Hadza Men’s Work.” Human Nature 25, no. 4 (2014): 620–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12110-014-9218-z.

Zahavi, Amotz, and Avishag Zahavi. The Handicap Principle: a Missing Piece of Darwin's Puzzle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.