Mammoths and the Myth of Wilderness

We need the tonic of wildness -- to wade sometimes in marshes where the bittern and the meadow-hen lurk, and hear the booming of the snipe; to smell the whispering sedge where only some wilder and more solitary fowl builds her nest, and the mink crawls with its belly close to the ground. At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be infinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature." ~Henry David Thoreau

When Thoreau penned those words, he was a fish swimming against the current. He was writing in a Victorian world caught in the stream of the industrial revolution, modernizing, urbanizing, and colonizing. Today, we see wilderness as something precious. It is a threatened, pristine place where one half expects David Attenborough’s voice to come echoing through the trees. To early American pioneers, wilderness was a terrifying adversary, not a thing to be enjoyed. Compared with the pastoral order of the European countryside, “the seemingly boundless wilderness of the New World was something else. In the face of this vast blankness, courage failed and imagination multiplied fears” (Nash 2014, 26). Wilderness was set in opposition to civilization, and became an obstacle to overcome on the road to progress. Lewis Cass, the American Secretary of War stated in 1830 that “there can be no doubt, and such are the views of the elementary writers upon the subject, that the Creator intended the earth should be reclaimed from a state of nature and cultivated” (Cass 1830, 77).

In July of 1845 Thoreau began his seclusion near Walden Pond. That same year, in fact, that very same month, an essay titled Annexation was published in the United States Magazine and Democratic Review. Its author, John O’Sullivan, was a nationalistic American columnist, descended from a colorful line of Irish expatriates and soldiers of fortune. Born at sea, he was the son of American diplomat and Sea captain John Thomas O’Sullivan, the third O’Sullivan Baronet of his name. O’Sullivan had his father’s aristocratic manner, and he was a fervent advocate for the prosecution of the Mexican-American War, and later, for the Confederate cause in the Civil War. His name would have been largely forgotten by historians had he not coined one of the most famous ideas in American history: Manifest Destiny. In Annexation, he made the case that it was the manifest destiny of the Anglo-Saxon race to spread across the whole of the American continent “to the possession of the homes conquered from the wilderness by their own labors and dangers, sufferings and sacrifices” (O'Sullivan 1845, 9).

As this rapacious expansion whittled away North America’s wild lands, evidence of the continent’s great antiquity was already available. A century earlier, in the summer of 1705, a Dutch farmer found a mass of cyclopean bones eroding from the bank of the Hudson River, near the town of Claverack. In July 1706, more bones were found near Coxsackie, just a day’s travel North of the original find. Word spread quickly, and as locals collected the bones, naturalists and educated men began to take notice. A great tooth from Claverack came into the possession of Edward Hyde, the British Governor of New York Province, who shipped it along to the British Royal Society, packed in a box labeled “tooth of a giant” (Semonin 2000, 15). Based on a biblical view of natural history, he believed that it was the tooth of a giant that lived before the Great Flood. This was not an uncommon interpretation. Governor Joseph Dudley of Massachusetts described the remains to his friend, the Reverend Cotton Mather. “I am perfectly of the opinion, that the tooth will agree only to a human body, for whom the flood only could prepare a funeral; and without doubt he waded as long as he could to keep his head above the clouds, but must at length be confounded with all other creatures, and the new sediment after the flood gave him the depth we now find” (Taylor et al 1959, 50).

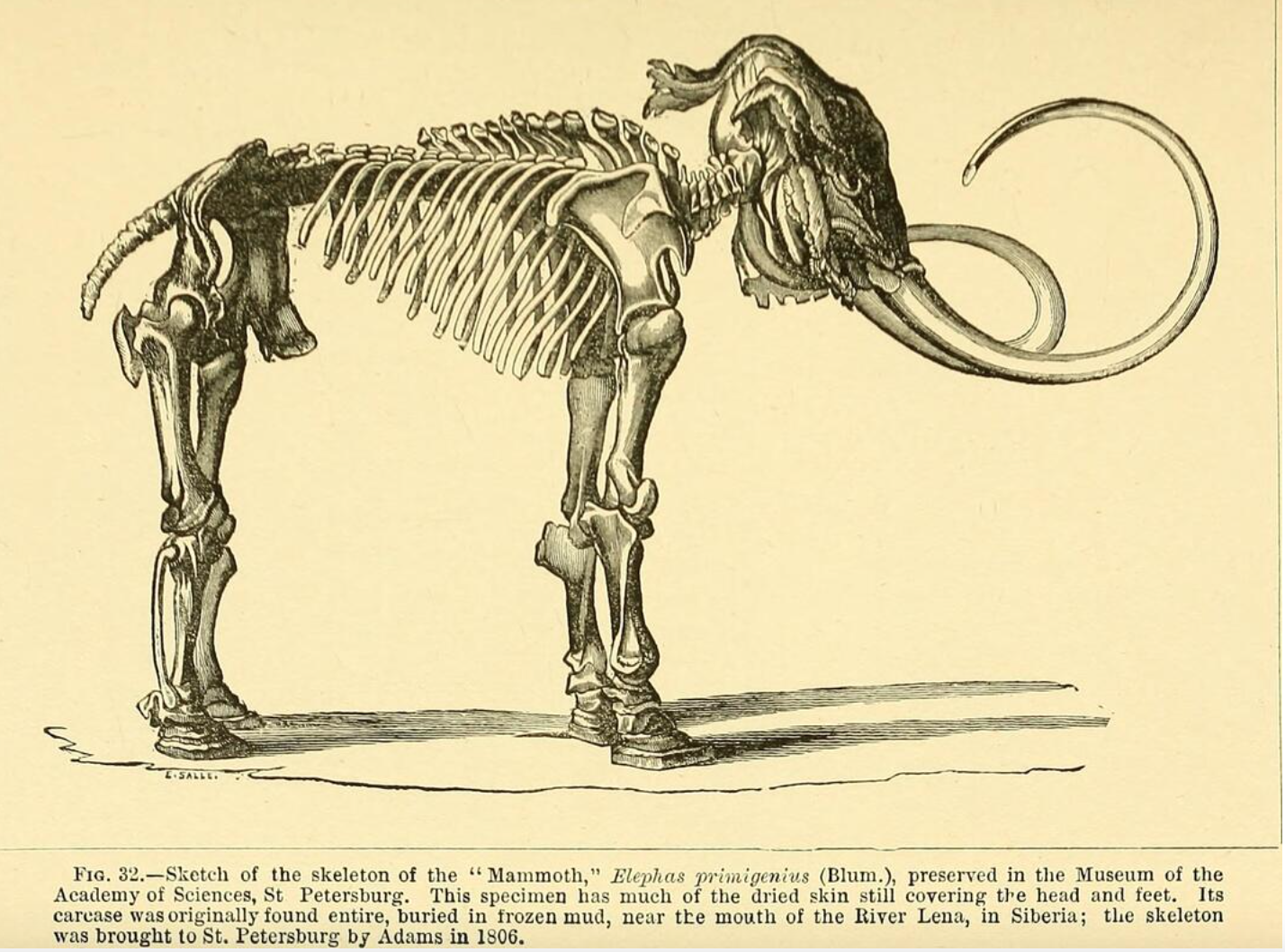

Less than a decade later across the Atlantic, in northern Ireland in the County Cavan, a jaw and teeth were uncovered by mill workers digging a foundation. Several of the teeth came into the possession of the Dublin surgeon Thomas Molyneux, who published an interpretation of the bones in 1715. He based his analysis on comparative anatomy, and quickly became “pretty well convinced they must have been the Grinding Teeth of an Elephant” (Molyneux 1715, 371). Such discoveries were novel in the American colonies, but fossil ivory had been exported from Siberia since antiquity. From at least the time of Peter the Great, reports had filtered into Europe of great bones eroding from the permafrost, which the Mongolians called mammut. In Siberian folklore, they were thought to be a burrowing creature. While Molyneux dismissed the idea that these were the bones of a giant, or some Siberian troglodyte as a groundless claim, he struggled to explain how elephants could have once lived so far north. He wondered at the possibility that “this Terraqueous Globe might, in the earliest Ages of the World, after the Deluge, but before all Records of our oldest Histories, differ widely from its present Geography” (Molyneux 1715, 378).

Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon was one of the first to suggest that species could die out. In the ninth volume of his Histoire naturelle, he alluded to fossil elephants such as those found at Claverack and the County Cavan (Buffon 1749-88 vol. 9, 126). He grappled with the possibility that these represented an extinct species, but ultimately rejected the idea. Buffon and his anatomist Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton concluded that “the difference in size, which appeared excessive, seemed sufficient to attribute this bone to another animal that ought to be larger than the elephant. But, since no one knew of any larger animal, it was necessary to resort to the fictitious mammout: this fabulous animal has been imagined in the northern countries, where there are found very frequently the bones, teeth, and tusks of the elephant” (Buffon 1749-88 vol. 11, 170). It was not until 1796, that French anatomist Georges Cuvier revived the idea. He suggested that these were not simply elephant bones found improbably far north, but represented an extinct species (Rudwick 1997). Actually, he identified two distinct species. The Eurasian variety as Mammoth, and the American specimens as Mastodon. When the bones of another great mammal were discovered in northern Argentina, on the bank of the river Luján, Cuvier identified it as an extinct species of giant ground sloth, which he named Megatherium. Evidence was emerging that natural ecosystems could change, and that the landscapes which American frontiersman were settling had once looked quite different.

By the late nineteenth century, there was a growing awareness that the American frontier was not boundless or inexhaustible. As concerns for the preservation of America’s remaining wilderness mounted, Thoreau’s romantic exaltation of the natural world began to enter the mainstream, expressed by men like John Burroughs, John Muir, Teddy Roosevelt, and Aldo Leopold. When visiting the Sierra Nevadas in 1869, John Muir exclaimed that “No description of Heaven that I have ever heard or read of seems half so fine” (Muir 1911, 211). In 1887, Roosevelt founded the first conservation organization in the United States, the Boone and Crockett Club. A few years later in the 1890 census, the director of the U.S. Census Bureau announced that the western Frontier was closed. For a nation that had identified with O’Sullivan’s vision of Manifest Destiny, this was the end of an epoch. The historian Frederick Jackson Turner capitalized on the census bureau’s announcement, and published his Frontier Thesis in 1893. According to Turner, the egalitarianism, distain for high culture, and love of freedom which characterized American life was a result of the constant access to an untouched frontier with land and resources that never seemed to end. “American democracy was born of no theorists dream; it was not carried in the Susan Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier” (Turner 1920, 293). If the wilderness was what gave Americans their unique character, then its destruction was a crime. Aldo Leopold lamented that: “Man always kills the thing he loves, and so we the pioneers have killed our wilderness. Some say we had to. Be that as it may, I am glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in. Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?” (Leopold 1949, 157)

To white settlers, the American wilderness was a bottomless, untouched trove of resources, frontiers and unfinished maps. Of course, this supposed wilderness was already occupied. 19th century depictions of the indigenous people who found themselves on the wrong side of the colonial encounter painted them as child-like and incapable of advancement. Lewis Cass said of them: “they are in a state of nature, as much so as it is possible for any people to be” (Cass 1830, 74). Influential anthropologists of the day, such as Lewis Henry Morgan and Edward Burnett Tylor, believed that Native Americans could be classified somewhere between savagery and barbarism, with the lowest among them described as little more than animals. Tylor noted that “there are several great linguistic families whose members were discovered in a savage state” throughout North America (Tylor 1871, 52). By these accounts Native Americans were just a feature of the wilderness they inhabited. For men like Roosevelt and Turner, this was implicit in their worldview.

This view has long since been banished from academic discourse. Modern archaeological research has proven that Native Americans were adept shapers of their environments. They have transformed ecosystems since they first penetrated the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets at least 15,000 years ago (and perhaps much earlier). By 10,350 years ago, humans were cultivating wild plants across the Amazon in artificial raised forest islands, altering the balance of ecosystems (Lombardo et al 2020). Fire regimes in California (Klimaszewski-Patterson and Mensing 2020) and the Great Plains (Roos et al 2018) were re-written by foragers, dictating landscape compositions for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. Ecosystems along the Mississippi were shaped by Maize farmers (Aiuvalasit et al 2020), and the Maya cleared forests and altered water tables in ancient Mesoamerica (Battistel et al 2018).

The La Brea Tar Pits by Charles Knight, 1921

Since Cuvier's time, we have identified dozens of species of megafauna which went extinct in the Americas by the end of the last ice age. Many researchers believe that humans contributed to the extinction of some, or perhaps all, of these megafauna. If this is true, then the ecosystems of North and South America have not been untouched since the first Paleoindians paddled up the Columbia River, or penetrated the rainforests of South America. If there is a wilderness for us to romanticize and to dream of restoring, it is not the ‘wilderness’ that European settlers encountered as they conquered North America. It is a much older wilderness, as old as the first Americans. The end of that wilderness was the extinction of the menagerie of giants that once roamed the continent.

References:

Aiuvalasit, Michael, Tim Riley, and Joseph Schuldenrein. “Multiproxy Evidence for Rapid and Enduring Anthropogenic Vegetation Change during the Late Holocene from an Abandoned Channel of the Mississippi River, Wapanocca Bayou, Arkansas, USA.” Geoarchaeology 35, no. 3 (2020): 351–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21773.

Argot, Christine. “Changing Views in Paleontology: The Evolution of a Giant (Megatherium, Xenarthra).” Essay. In Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology A Tribute to Frederick S. Szalay, edited by Eric J. Sargis and Marian Dagosto. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2008.

Battistel, D., M. Roman, A. Marchetti, N. M. Kehrwald, M. Radaelli, E. Balliana, G. Toscano, and C. Barbante. “Anthropogenic Impact in the Maya Lowlands of Petén, Guatemala, during the Last 5500 Years.” Journal of Quaternary Science 33, no. 2 (2018): 166–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3013.

Buffon, George Louis Leclerc de. Histoire Naturelle, generale et particuliere. 44 vols. Paris: Imprimeries royale, 1749-88

Cass, Lewis. “Removal of the Indians,” North American Review 30 (1830)

Klimaszewski-Patterson, Anna, and Scott Mensing. “Paleoecological and Paleolandscape Modeling Support for Pre-Columbian Burning by Native Americans in the Golden Trout Wilderness Area, California, USA.” Landscape Ecology 35, no. 12 (2020): 2659–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01081-x.

Lombardo, Umberto, José Iriarte, Lautaro Hilbert, Javier Ruiz-Pérez, José M. Capriles, and Heinz Veit. “Early Holocene Crop Cultivation and Landscape Modification in Amazonia.” Nature 581, no. 7807 (2020): 190–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2162-7.

Muir, John. My First Summer in the Sierra (1911), reprinted in John Muir: The Eight Wilderness Discovery Books (London, England: Diadem; Seattle, Washington: Mountaineers, 1992), P. 211.

Molyneux, John. “Remarks upon aforsaid Letter and Teeth, by Thomas Molyneux, M.D. and R.S.S. Physician to the State of Ireland: Addres’d to his Grace the Lord Archbishop of Dublin,” Philosophical Transcations 29 (1715): 371

Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

O'Sullivan, John. "Annexation" United States Magazine and Democratic Review (1845)

Roos, Christopher I., María Nieves Zedeño, Kacy L. Hollenback, and Mary M. Erlick. “Indigenous Impacts on North American Great Plains Fire Regimes of the Past Millennium.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 32 (2018): 8143–48. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805259115.

S., Rudwick Martin J. Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes, 1998.

Semonin, Paul. American Monster: How the Nation's First Prehistoric Creature Became a Symbol of National Identity. New York: New York University Press, 2000.

Taylor, Edward, Donald E. Stanford, and J. Dudley. “The Giant Bones of Claverack, New York, 1705.” New York History 40, no. 1 (1959): 47-61. Accessed August 24, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23153528.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. The Frontier in American History.